Introduction

Direct path insert is the ability to bypass the shared buffers while inserting data.

It writes the data into brand new pages and appends them direcly into the relation files.

This is not to be confused with Direct I/O (which bypass the kernel page cache).

In this post we will:

- look at the pros and cons

- introduce a new PostgreSQL module that provides direct path insert

- look at an example and explain the performance results

Let’s see the pros and cons

Pros

- Time saving bypassing the shared buffers machinery (search for a buffer, acquire a buffer and so on…)

- Time saving bypassing the search of existing block(s) with enough free space

- The shared buffers area is not populated with “useless” data that you may don’t want to query anytime soon

Cons

- If the data set being inserted is too small:

- direct path insert is not always faster

- you can waste space on disk (for example if you direct path insert only one row then you still allocate a brand new page just for this single row)

- An access exlusive lock is acquired on the relation during the insert, so:

- you can not query the relation

- you can not insert/update/delete or merge on the relation

- only one direct path insert can run on the same relation at the same time

Please bear in mind that a partition is considered as a relation (so that you can direct path insert to multiple partitions at the same time).

How can it be tested?

It can be tested with a new pg_directpaths PostgreSQL module (that does not require any core changes). The module can be found here and supports PostgreSQL versions >= 10.

You just need to add a new /*+ APPEND */ hint to your insert statement to give it a try.

Please note that at the time of this writing the module is in alpha version and should not be used for Production.

Currently this module has some limitations (that will be addressed in the near future):

- the /*+ APPEND */ hint is ignored if the insert is done on a partitioned table

- check constraints are ignored

- all the relation’s indexes are rebuild (even if you direct path insert a single row)

But already provides some benefits:

- All the ones already mentioned in the Pros section, plus:

- If the data set being inserted is large enough:

- faster WAL logging (as it is done by batch of Full Page Images and not record by record)

- less amount of WAL generated (same reason as above)

Let’s look at an example

The following has been done on PostgreSQL version 14.3.

- With a standard insert

postgres=# create table desttable (timeid integer,insid integer,indid integer,value integer);

CREATE TABLE

postgres=# select pg_current_wal_lsn(); \gset

pg_current_wal_lsn

--------------------

9/131CFE90

(1 row)

postgres=# \timing

Timing is on.

postgres=# insert into desttable select a % 50, a % 10000, a , a from generate_series(1,50000000) a;

INSERT 0 50000000

Time: 111759.420 ms (01:51.759)

postgres=# select pg_size_pretty(pg_wal_lsn_diff(pg_current_wal_lsn(),:'pg_current_wal_lsn')) ;

pg_size_pretty

----------------

3443 MB

(1 row)

Time: 0.622 ms

as you can see it took about 111 seconds to insert the data (50M tuples) and it generated about 3.5 GB of WAL.

- With direct path insert

postgres=# create table desttable (timeid integer,insid integer,indid integer,value integer);

CREATE TABLE

postgres=# select pg_current_wal_lsn(); \gset

pg_current_wal_lsn

--------------------

9/EA524F40

(1 row)

postgres=# \timing

Timing is on.

postgres=# /*+ APPEND */ insert into desttable select a % 50, a % 10000, a , a from generate_series(1,50000000) a;

INSERT 0 50000000

Time: 56424.362 ms (00:56.424)

postgres=# select pg_size_pretty(pg_wal_lsn_diff(pg_current_wal_lsn(),:'pg_current_wal_lsn')) ;

pg_size_pretty

----------------

2114 MB

(1 row)

Time: 0.503 ms

postgres=# \dt+ desttable

List of relations

Schema | Name | Type | Owner | Persistence | Access method | Size | Description

--------+-----------+-------+----------+-------------+---------------+---------+-------------

public | desttable | table | postgres | permanent | heap | 2111 MB |

(1 row)

as you can see it took about 56 seconds to insert the same amount of data (50M tuples) and it generated about 2.1 GB of WAL.

-

So, to compare both inserts:

- it took about 111 seconds to run for the standard insert and about 56 seconds to run with the direct path insert

- it generated less amount of WAL with the direct path insert (for the reason explained above)

Why did the direct path insert run faster?

First let’s have a look to the wait events history while the standard insert was running.

To do so, let’s query the pg_active_session_history view coming with the pgsentinel extension:

postgres=# select wait_event,count(*),top_level_query from pg_active_session_history group by wait_event,top_level_query;

wait_event | count | top_level_query

------------+-------+-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

WALSync | 1 | insert into desttable select a % 50, a % 10000, a , a from generate_series(1,50000000) a;

WALWrite | 12 | insert into desttable select a % 50, a % 10000, a , a from generate_series(1,50000000) a;

CPU | 98 | insert into desttable select a % 50, a % 10000, a , a from generate_series(1,50000000) a;

(3 rows)

As you can see almost 88% of the time has been spent in the CPU.

Then it makes a lot of sense to compare 2 Flame Graphs:

- one captured while the standard insert was running:

- the second one, captured while the direct path insert was running:

For the interpretation, you can assume that the IAExecInsert seen in the direct path one relates to the ExecInsert in the standard one.

Then, as you can see in the standard insert, a large part of the ExecInsert samples are linked to RelationGetBufferForTuple and XLogInsert (mainly XLogInsertRecord) while we don’t see any of those in the direct path one. This is the result of bypassing the shared buffers and WAL logging by batch of Full Page Images (instead of record by record).

Simply put, this is where the saving is coming from: the direct path insert has been faster because it did less work.

Conclusion

In this blog post we have seen:

- the direct path insert concept

- the pros and cons of direct path insert

- that it can be implemented in a module thanks to the power of the PostgreSQL extensibility

- an example and the reason(s) why direct path insert has been faster (than the standard insert)

Direct path inserts should be used with care and in the proper circumstances.

If done that way, it could provide huge performance benefits.

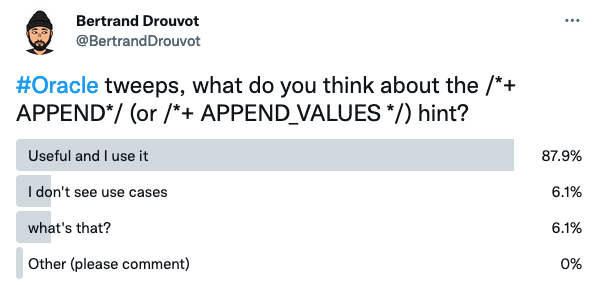

It has been around for a while in the Oracle world and seems well known and used:

at least according to some of my Oracle tweeps ![]() .

.