INTRODUCTION

This blog post came to my mind following an interesting conversation I have had on twitter with Philippe Fierens and Karl Arao.

Let’s go for it:

Nowadays it is very common to consolidate multiple databases on the same server.

One could want to limit the CPU usage of databases and/or ensure guarantee CPU for some databases. I would like to compare two methods to achieve this:

- Instance Caging (available since 11.2).

- processor_group_name (available since 12.1).

This blog post is composed of 4 mains parts:

- Facts: Describing the features and a quick overview on how to implement them.

- Observations: What I observed on my lab server. You should observe the same on your environment for most of them.

- OEM and AWR views for Instance Caging and processor_group_name with CPU pressure.

- Customer cases: I cover all the cases I faced so far.

FACTS

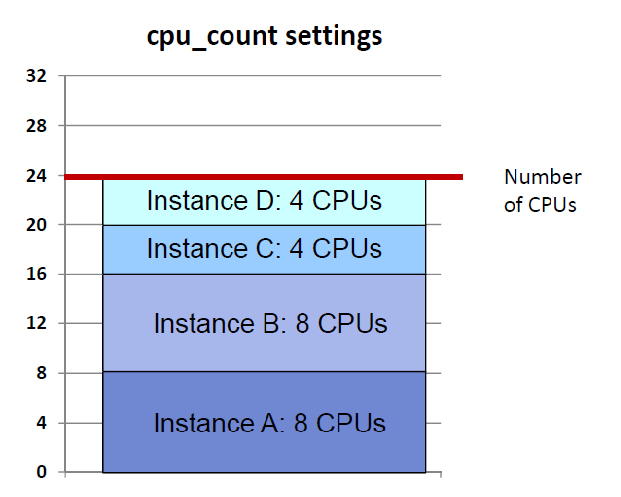

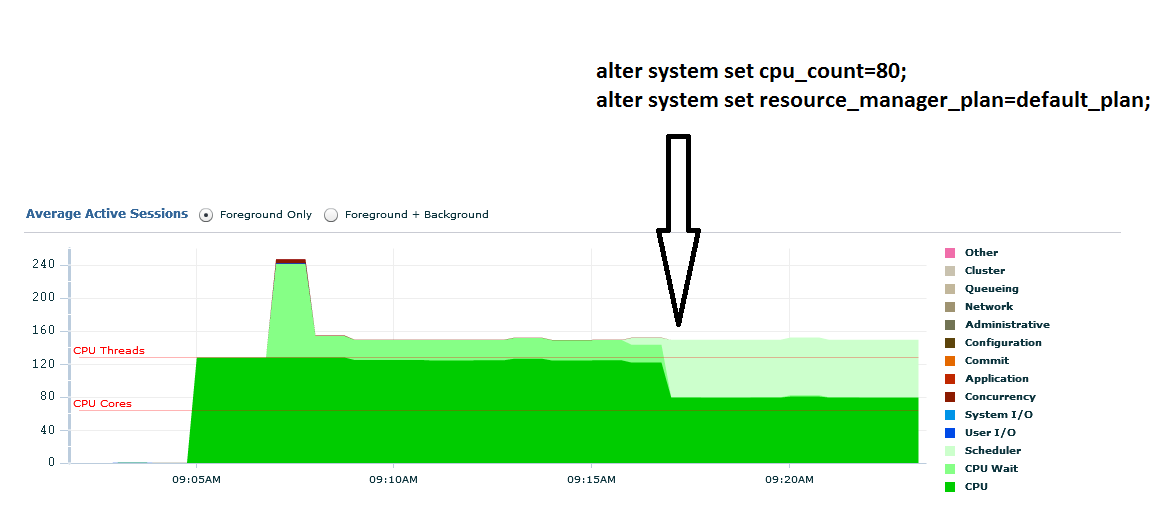

Instance caging: Purpose is to Limit or “cage” the amount of CPU that a database instance can use at any time. It can be enabled online (no need to restart the database) in 2 steps:

- Set “cpu_count” parameter to the maximum number of CPUs the database should be able to use (Oracle advises to set cpu_count to at least 2)

SQL> alter system set cpu_count = 2;

- Set “resource_manager_plan” parameter to enable CPU Resource Manager

SQL> alter system set resource_manager_plan = ‘default_plan’;

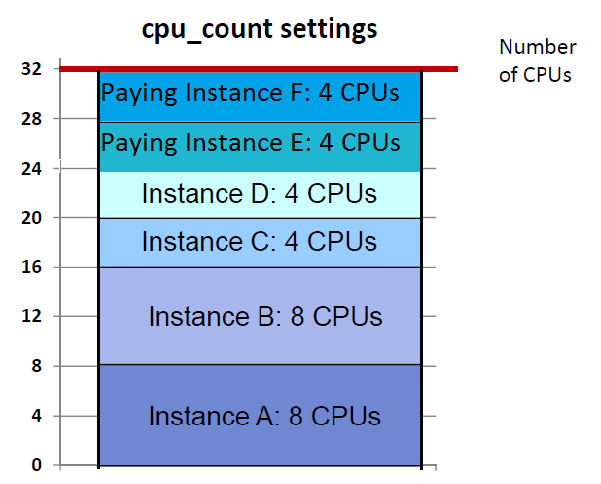

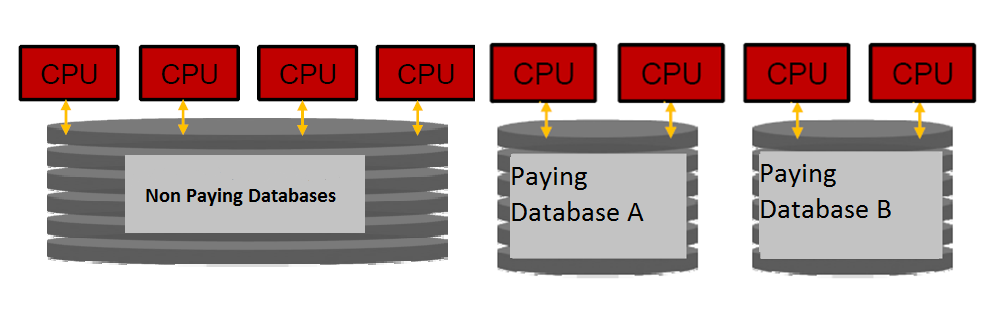

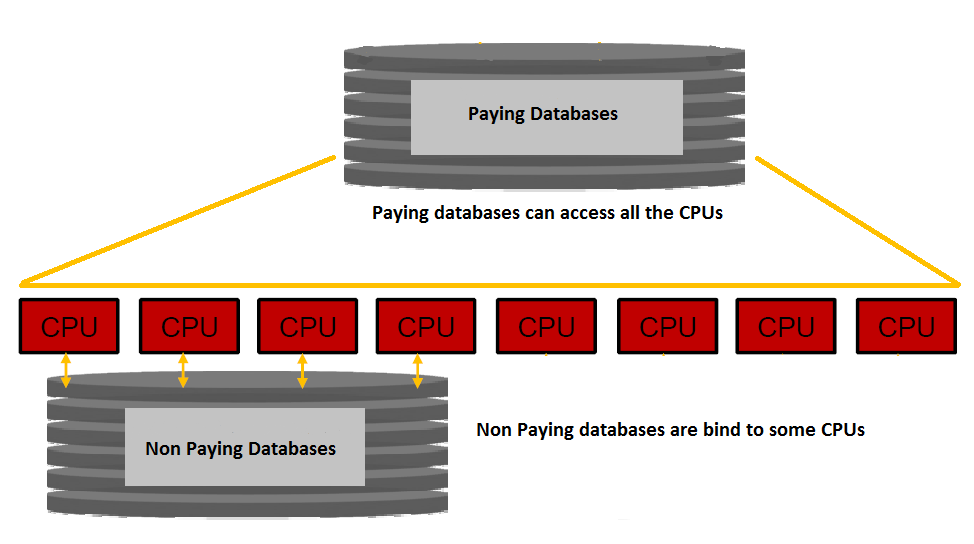

Graphical view with multiple databases limited as an example:

- Specify the CPUs or NUMA nodes by creating a “processor group”:

Example: Snippet of /etc/cgconfig.conf:

group oracle {

perm {

task {

uid = oracle;

gid = dc_dba;

}

admin {

uid = oracle;

gid = dc_dba;

}

}

cpuset {

cpuset.mems=0;

cpuset.cpus="1-9";

}

}

- Start the cgconfig service:

service cgconfig start

- Set the Oracle parameter “processor_group_name” to the name of this processor group:

SQL> alter system set processor_group_name='oracle' scope=spfile;

- Restart the Database Instance.

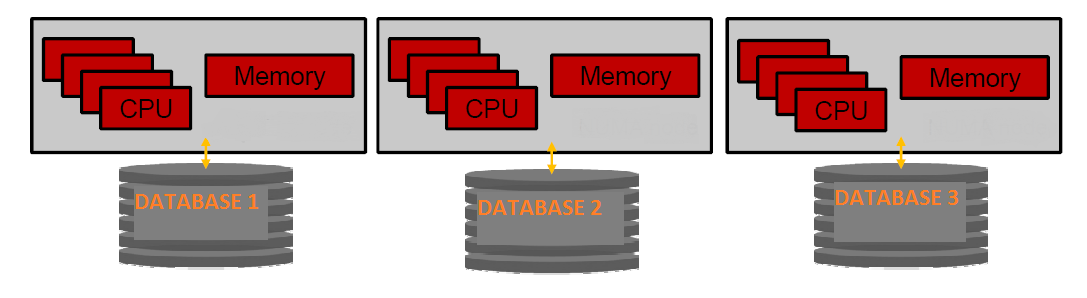

Graphical view with multiple databases bound as an example:

Remark regarding the Database Availability:

- The Instance caging can be enabled online.

- For cgroups/processor_group_name the database needs to be stopped and started.

OBSERVATIONS

For brevity, “Caging” is used for “Instance Caging” and “Binding” for “cgroups/processor_group_name” usages.

Also “CPU” is used when CPU threads are referred to, which is the actual granularity for caging and binding.

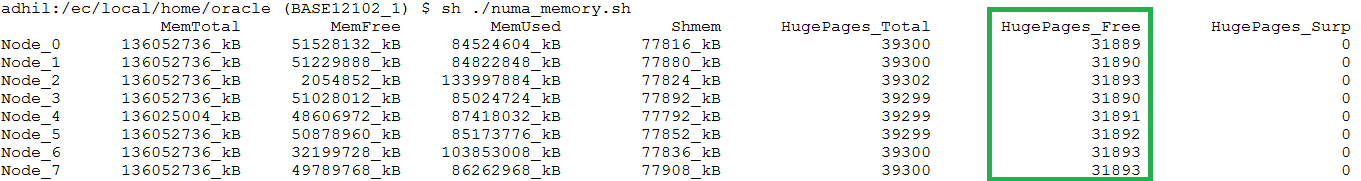

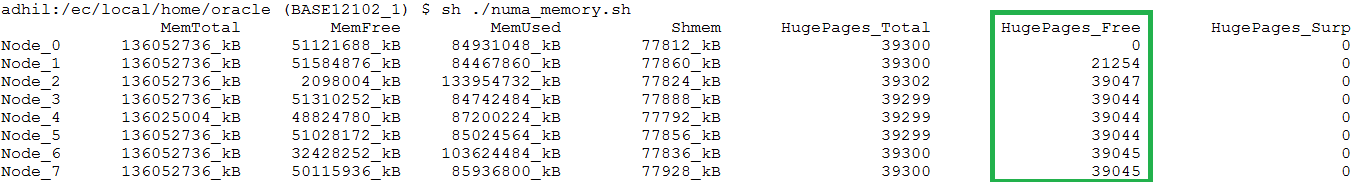

The observations have been made on a 12.1.0.2 database using large pages (use_large_pages=only). I will not cover the “non large pages” case as not using large pages is not an option for me.

1. When you define the cgroup for the binding, you should pay attention to the NUMA memory and CPUs locality as it has an impact on the LIO performance (See this blog post). As you can see (on my specific configuration), remote NUMA nodes access has been slower by about 2 times compare to local access.

2.Without binding, the SGA is interleaved across all the NUMA nodes (unless you set the oracle hidden parameter _enable_NUMA_interleave to FALSE):

3.With binding (on more than one NUMA nodes), the SGA is not interleaved across all the NUMA nodes (SGA bind on nodes 0 and 1):

4.Instance caging has been less performant (compare to the cpu binding) during LIO pressure (by pressure I mean that the database needs more cpu resources than the ones it is limited to use) (See this blog post for more details). Please note that the comparison has been done on the same NUMA node (to avoid binding advantage over caging due to observations number 1 and 2).

5.With cpu binding already in place (using processor_group_name) we are able to change the number of cpus a database is allowed to use on the fly (See this blog post).

Remarks:

- You can find more details regarding observations 2 and 3 into this blog post.

- From 2 and 3 we can conclude that with the caging, the SGA is interleaved across all the NUMA nodes (unless the caging has been setup on top of the binding (mix configuration)).

- All above mentioned observations are related to performance. You may want to run the tests described in observations 1 and 4 in your own environment to measure the actual impact on your environment.

Caging and Binding with CPU pressure: OEM and AWR views

What do the OEM or AWR views of a database being under CPU pressure show (pressure meaning the database needs more CPU resources than it is configured to use) with both caging and binding? Let’s have a look.

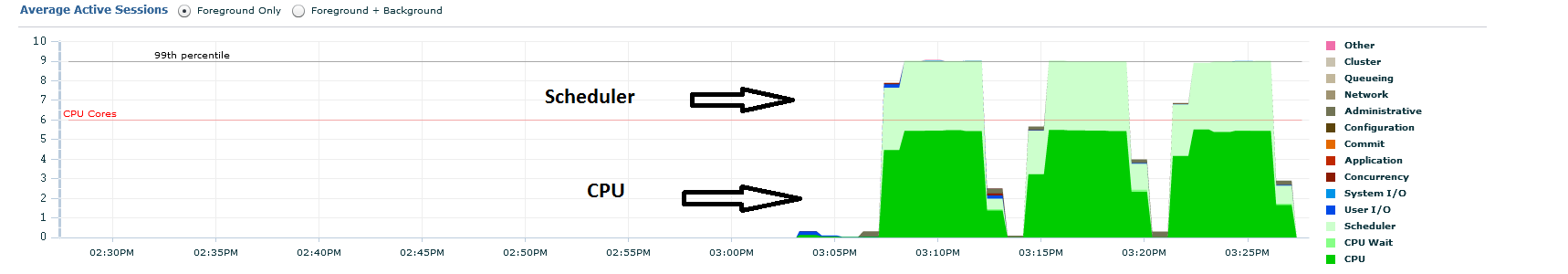

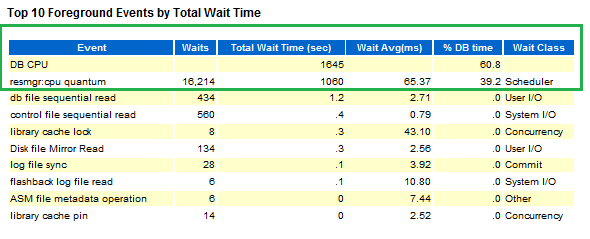

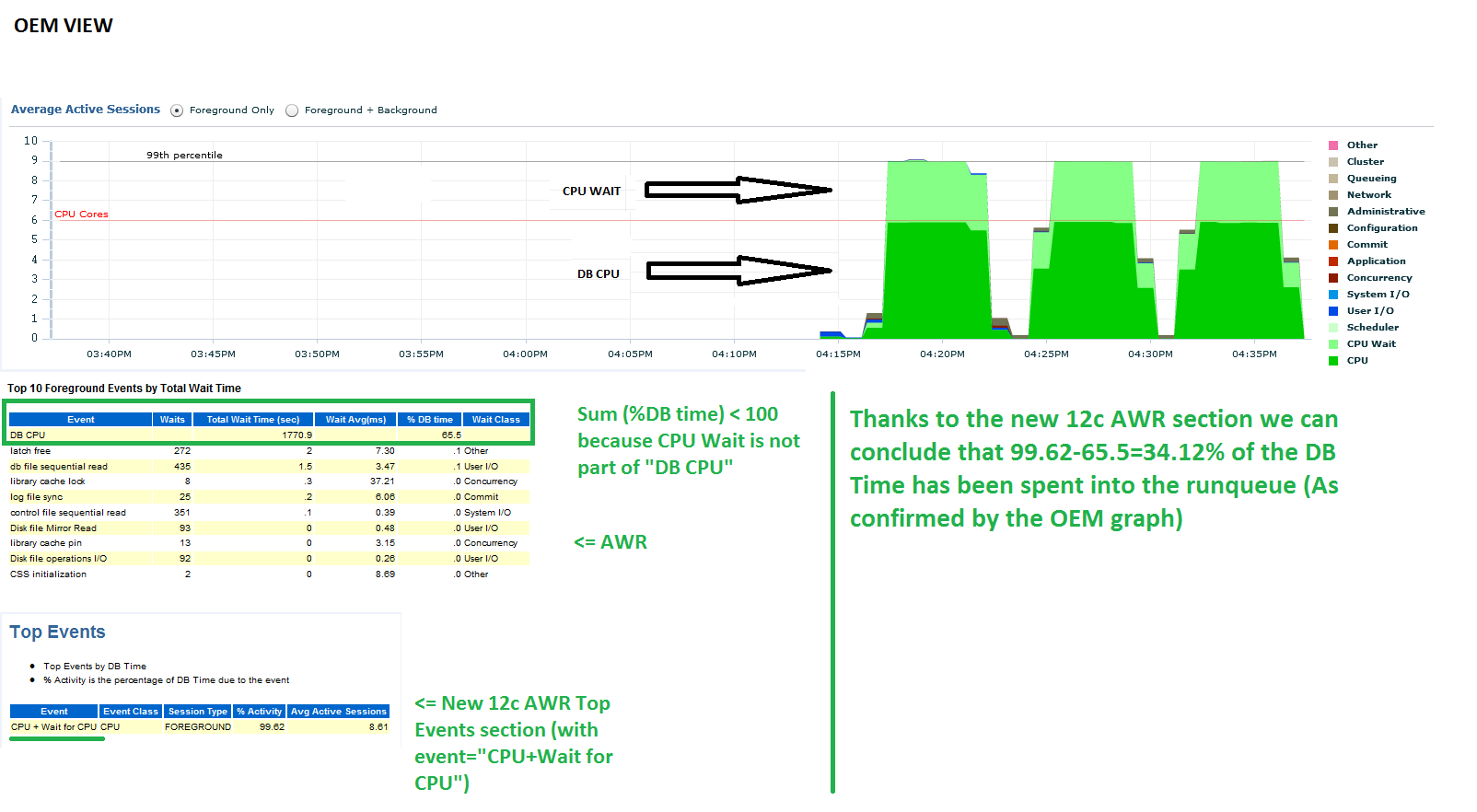

CPU pressure with Caging:

The database has the caging enabled with the cpu_count parameter set to 6 and is running 9 SLOB users in parallel.

The OEM view:

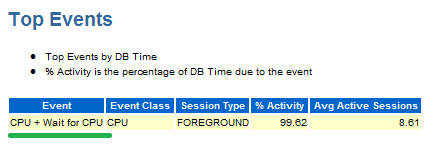

The AWR view:

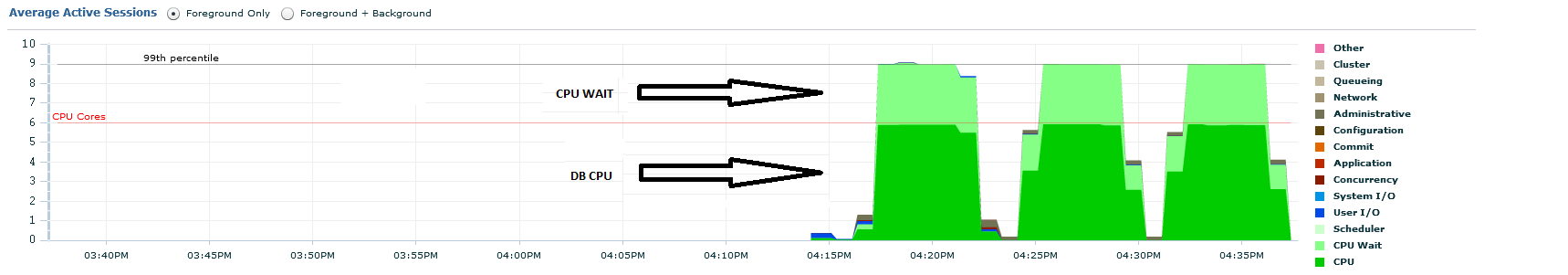

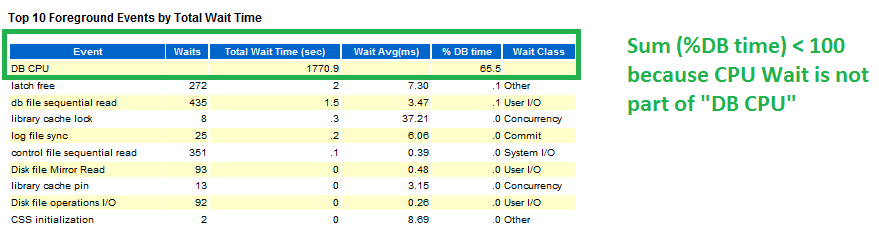

CPU pressure with Binding:

The processor_group_name is set to a cgroup of 6 CPUs. The Instance is running 9 SLOB users in parallel.

The OEM view:

The AWR view:

To summarize:

- 65.5% of the DB time has been spent on the CPU.

- 99.62–65.5 = 34.12% of the DB time has been spent into the runqueue.

CUSTOMER CASES

The cases below are based on studies for customers.

Case number 1: One database uses too much CPU and affects other instances’ performance.** **

Then we want to limit its CPU usage:

- Caging: We are able to cage the database Instance without any restart.

- Binding: We are able to bind the database Instance, but it needs a restart.

Example of such a case by implementing Caging:

What to choose?

What to choose?

The caging is the best choice in this case (as it is the easiest and we don’t need to restart the database).

For the following cases we need to define 2 categories of database:

- The paying ones: Customer paid for guaranteed CPU resources available.

- The non-paying ones: Customer did not pay for guaranteed CPU resources available.

Case number 2: Guarantee CPU resource for some databases. The CPU resource is defined by the customer and needs to be guaranteed at the database level.

Caging:

- All the databases need to be caged (if not, there is no guaranteed resources availability as one non-caged could take all the CPU).

- As a consequence, you can’t mix paying and non-paying customer without caging the non-paying ones.

- You have to know how to cage each database individually to be sure that sum(cpu_count) <= Total number of threads (If not, CPU resources can’t be guaranteed).

- Be sure that sum(cpu_count) of non-paid <= “CPU Total – number of paid CPU” (If not, CPU resources can’t be guaranteed).

- There are a maximum number of databases that you can put on a machine: As cpu_count >=2 (see facts) then the maximum number of databases = Total number of threads /2.

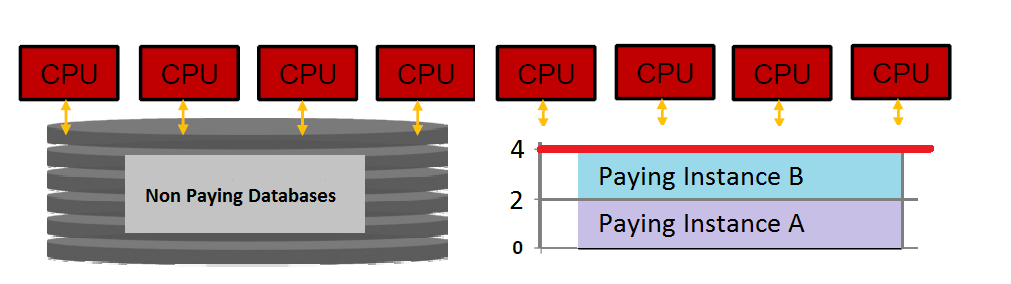

Graphical view as an example:

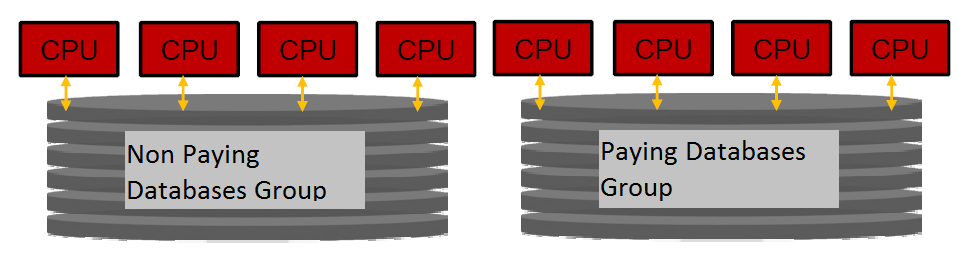

Binding:

Each database is linked to a set of CPU (There is no overlap, means that a CPU can be part of only one cgroup). Then, create:

- One cgroup per paying database.

- One cgroup for all the non-paying databases.

That way we can easily mix paying and non-paying customer on the same machine.

Graphical View as an example:

- A non-paying one: Put it into the non-paying group.

- A paying one: Create a new cgroup for it, assigning CPU taken away from non-paying ones if needed.

Binding + caging mix:

- create a cgroup for all the paying databases and then put the caging on each paying database.

- Put the non-paying into another cgroup (no overlap with the paying one) without caging.

Graphical View as an example:

- A non-paying one: Put it into the non-paying group.

- A paying one: Extend the paying group if needed (taking CPU away from non-paying ones) and cage it accordingly.

What to choose?

I would say there is no “best choice”: It all depends of the number of database we are talking about (For a large number of databases I would use the mix approach). And don’t forget that with the caging option your can’t put more than number of threads/2 databases.

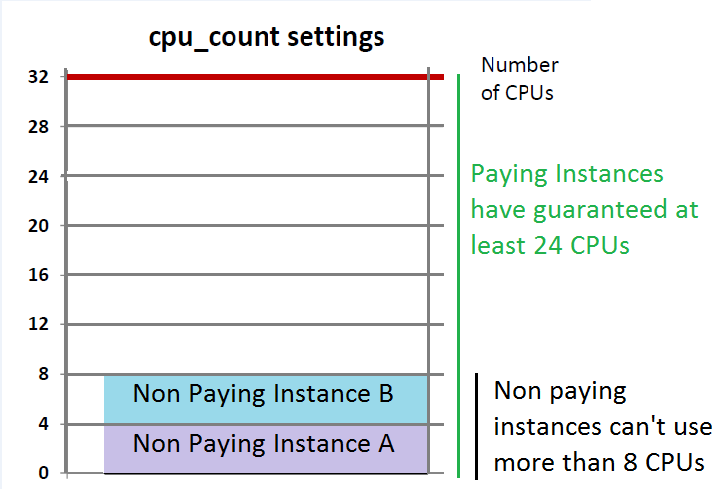

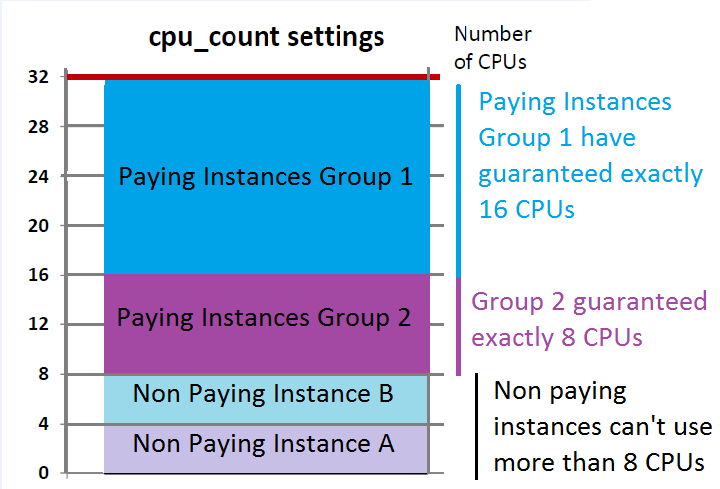

Case number 3: Guarantee CPU resource for exactly one group of databases. The CPU resource needs to be guaranteed at the group level (Imagine that customer paid for 24 CPUs whatever the number of database is).

Caging:

We have 2 options:

1. Option 1:

- Cage all the **non-paying databases.

** - Be sure that sum(cpu_count) of non-paid <= “CPU Total – number of paid CPU” (If not, CPU resources can’t be guaranteed).

- Don’t cage the paying databases.

That way the paying databases have guaranteed at least the resources they paid for.

Graphical View as an example:

- A non-paying one: Cage it but you may need to re-cage all the non-paying ones to guarantee the paying ones still get its “minimum” resource.

- A paying one: Nothing to do.

2. Option 2:

- Cage all the databases (paying and non-paying).

- You have to know how to cage each database individually to be sure that sum(cpu_count) <= Total number of threads (If not, CPU resources can’t be guaranteed).

- Be sure that sum(cpu_count) of non-paid <= “CPU Total – number of paid CPU” (If not, CPU resources can’t be guaranteed).

That way the paying databases have guaranteed exactly the resources they paid for.

Graphical View as an example:

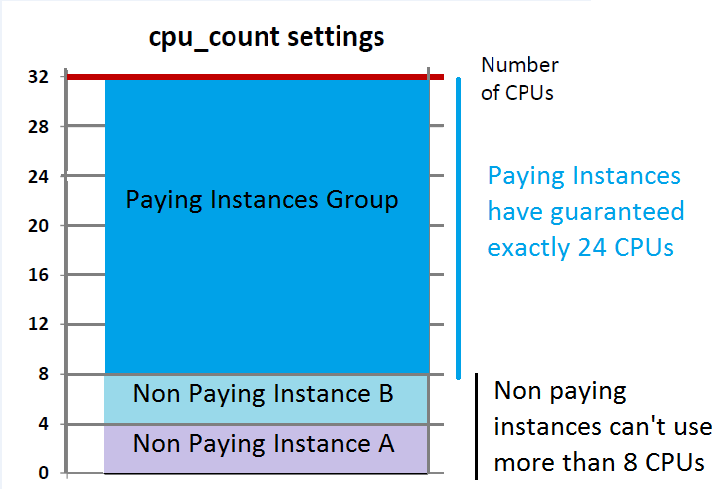

Binding:

Again 2 options:

1. Option 1:

- Put all the non-paying databases into a “CPU Total – number of paid CPU “ cgroup.

- Allow all the CPUs to be used by the paying databases (don’t create a cgroup for the paying databases).

- That way the paying group has guaranteed at least the resources it paid for.

Graphical View as an example:

- A non-paying one: Put it in the non-paying cgroup.

- A paying one: Create it outside the non-paying cgroup.

2. Option 2:

- Put all the paying databases into a cgroup.

- Put all the non-paying databases into another cgroup (no overlap with the paying cgroup).

That way the paying databases have guaranteed exactly the resources they paid for.

Graphical View:

- A non-paying one: Put it in the non-paying cgroup.

- A paying one: Put it in the paying cgroup.

Binding + caging mix:

I don’t see any benefits here.

What to choose?

I like the option 1) in both cases as it allows customer to get more than what they paid for (with the guarantee of what they paid for). Then the choice between caging and binding really depends of the number of databases we are talking about (binding is preferable and easily manageable for large number of databases).

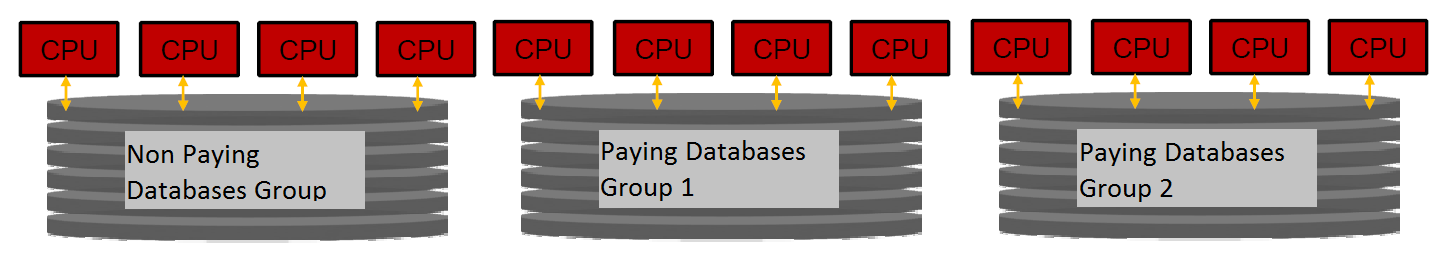

Case number 4: The need to guarantee CPU resources for more than one group of databases (Imagine that one group=one customer). The CPU resource needs to be assured at each group level.

Caging:

- All the databases need to be caged (if not, there is no guaranteed resources availability as one non-caged could take all the CPU).

- As a consequence, you can’t mix paying and non-paying customer without caging the non-paying ones.

- You have to know how to cage each database individually to be sure that sum(cpu_count) <= Total number of threads (If not, CPU resources can’t be guaranteed).

- Be sure that sum(cpu_count) of non-paid <= “CPU Total – number of paid CPU” (If not, CPU resources can’t be guaranteed).

- There are a maximum number of databases that you can put on a machine: As cpu_count >=2 (see facts) then the maximum number of databases = Total number of threads /2.

Graphical View as an example:

Overlapping is not possible in that case (means you can’t guarantee resources with overlapping).

Binding:

- Create a cgroup for each paying database group and also for the non-paying ones (no overlap between all the groups).

- Overlapping is not possible in that case (means you can’t guarantee resources with overlapping).

Graphical view as an example:

If you need to add a database, then simply put it in the right group.

Binding + caging mix:

I don’t see any benefits here.

What to choose?

It really depends of the number of databases we are talking about (binding is preferable and easily manageable for large number of databases).

REMARKS

- If you see (or faced) more cases, then feel free to share and to comment on this blog post.

- I did not pay attention on potential impacts on LIO performance linked to any possible choice (caging vs binding with or without NUMA). I just mentioned them into the observations, but did not include them into the use cases (I just discussed the feasibility of the implementation).

- I really like the options 1 into the case number 3. This option has been proposed by Karl during our conversation.

CONCLUSION

The choice between caging and binding depends of:

- Your needs.

- The number of databases you are consolidating on the server.

- Your performance expectations.

I would like to thank you Karl Arao, Frits Hoogland, Yves Colin and David Coelho for their efficient reviews of this blog post.